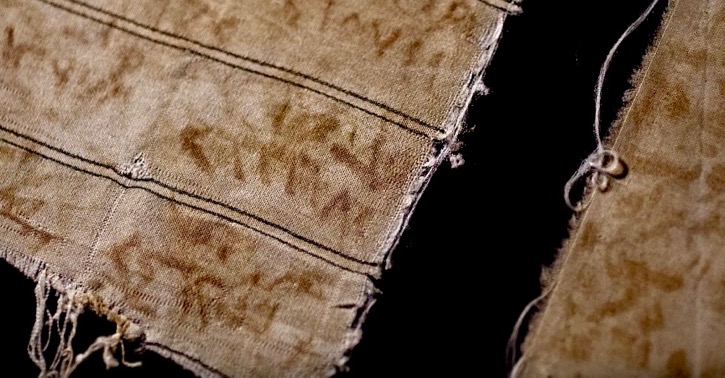

When Mansour Omari was released from a secret military prison in Syria after more than 300 days of imprisonment, he smuggled out the names of 82 prisoners written in blood and rust on ripped pieces of fabric. The pieces of cloth have been preserved in an exhibit by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM). (Image source: USHMM)

By Audrey Williams

When protests against the Syrian government broke out in 2011, activist and journalist Mansour Omari began documenting the names of Syrians who were disappeared by the Assad regime.

Then he became one of them.

A new documentary—82 Names: Syria, Please Don’t Forget Us—tells the story of Omari’s imprisonment and his efforts to document the atrocities the Assad regime has committed against the Syrian people. Last fall, the film was screened at multiple universities on the East Coast, including George Mason University on October 2, 2018.

Detained by military police in 2012, Omari spent more than 350 days in a secret, underground military prison. During his captivity, he and his fellow prisoners banded together to write down their names and smuggle them to the outside world so that their families would know what had happened to them.

They didn’t have paper, so they used ripped-up pieces of fabric. They didn’t have a pen, so they used chicken bone. They didn’t have ink, so they scrawled their names in blood, and they mixed it with rust to make the stain last.

They hid the five pieces of fabric with 82 names in the collar of a shirt and decided that whoever was released first would spirit the names out.

The responsibility fell to Omari. Before he left the prison, his cellmates told him, “Please don’t forget us.”

Telling stories to bear witness

In 82 Names, Omari strives to honor their appeal. The documentary tells the stories of victims of the Assad regime’s atrocities through interviews with Omari and other Syrian activists.

Directed by Iranian Canadian journalist and filmmaker Maziar Bahari, the documentary was developed in partnership with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) in Washington, D.C., which has preserved the five pieces of fabric as part of an exhibit.

“The purpose of the exhibit about Syria is to really be a voice for victims the way there was no voice for the Jews in the 1930s and 40s,” says Sara Bloomfield, director of the museum, in a clip from the documentary. Fifteen ‘chapters’ from the film have been made available to the public on the museum’s YouTube channel.

“I think one of the steps towards the aspiration of justice is just to acknowledge what happened, to remember the victims as individuals, not as statistics,” she says.

Like the exhibit, the documentary also draws parallels between the Assad regime’s atrocities and those carried out by the Nazi regime during the Holocaust. During the documentary, Omari visits the USHMM with Irene Weiss, a Holocaust survivor from Hungary who recounts her arrival at the Auschwitz death camp during the film.

The documentary also follows Omari as he travels to Germany, where he visits the Holocaust Memorial in Berlin and the Sachsenhausen concentration camp.

While visiting the exhibit at the USHMM, Omari discusses how the Syrian people “are neglected even in the Western media.”

“They focus on ISIS, they focus on military issues, not humanitarian issues or anything about Syrian civil society,” he says.

Omari was one of more than 100,000 people who have been ‘disappeared’ by the Assad regime since the start of the uprising in 2011. Declassified satellite imagery indicates that the regime has used a crematorium at Saydnaya military prison to hide the execution of thousands of prisoners.

According to Omari, the USHMM exhibit “can provide a small measure of symbolic justice to Syrians.”

Now, through screenings of 82 Names at universities around the U.S., the impact of the exhibit and Omari’s story is being widened.

Douglas Irvin-Erickson, an assistant professor at the School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution (S-CAR) at George Mason University and director of the school’s Genocide Prevention Program, organized the October screening of 82 Names on Mason’s Fairfax campus.

“The simple story of just how much the prisoners wanted the world to know their names speaks to the importance the victims of mass atrocity crimes place in bearing witness,” said Irvin-Erickson. “The path to reconciliation and peace in Syria […] will require a collective reckoning with the violence of the past, in terms of why it happened, how it happened, and what should be done so the society can move forward.”

This is a lesson he strives to instill in his students at Mason. He says the film makes clear how important it is in post-conflict situations to “establish a narrative of what happened that is built around facts, including historical and legal evidence, and the perspectives of the victims who suffered and survived.”

The responsibility and privilege of telling victims’ stories

Following the documentary’s screening at Mason, members of the audience—including students in Irvin-Erickson’s “Conflict and Our World” course (CONF 101)—heard from Bahari and Rafif Jouejati, co-founder and director of The Foundation to Restore Equality and Education in Syria (FREE-Syria).

Like Omari, Bahari has had personal experience with both state repression and having one’s story told through the medium of film.

Bahari spent three months in Evin prison in Iran after being arrested while covering the 2009 Iranian elections for Newseek. In his memoir, Then They Came for Me, Bahari recounts not only his ordeal in the prison but also that of his father, who was tortured in the prison under the Shah’s regime, and that of his sister, who was imprisoned in Evin during the Khomeini regime.

Bahari’s memoir was adapted into a motion picture by Jon Stewart. Though this film, Rosewater, was a fictionalized account rather than a documentary, Bahari sees parallels between it and 82 Names.

“[T]hat experience made me more aware that telling your story is both a big responsibility and also […] a great privilege,” Bahari told S-CAR News.

“It's a responsibility, because you just have to try to tell the truth as much as possible,” he said. “And also, it's a privilege, because not many people in the world have the opportunity to tell their stories to a large audience.”

Bahari, whose other films include Football, Iranian Style (2001) and Greetings from Sadr City (2007), sees films like 82 Names as “just one of many things that are happening in the world” to address the Syrian crisis.

“I think in order to have change, we need a sustained effort in order to inform people, expose people to reality, and also give people who don't have agency some sort of agency in order to express their ideas and thoughts,” he said.

With 82 Names, Bahari hopes that by “allowing Mansour and others to tell their stories,” he can help viewers “to understand the reality of what's going on in Syria a little bit better.”

The documentary left an impact on Connor Cuevo, a first-year Mason student majoring in Conflict Analysis and Resolution who attended the October screening.

“I already knew the things that the Assad regime was doing, but to see its impact up close like that, to see how visceral and real it was, was really very jarring,” he told S-CAR News, noting that his first reaction upon seeing the film was that “we’ve got to get justice for these people.”

The use of filmmaking as a storytelling medium struck Cuevo as well suited to the documentary’s message. “I do feel inspired that using personal testimony incorporated into a film is an effective means of mobilizing people to your cause,” he said.

For Cuevo, the film underlined that individuals’ stories have power when confronting conflict, a lesson he connects to his studies at Mason.

“In S-CAR, we kind of come from all walks of life, and I think it’s important that we use that to frame the multitudinous conflicts in the world,” he said.